The Secret Life of the Adder

Last year, at my local adder site, I helped out with their survey by supplementing their data with my own sightings, sending headshots of each individual I found. This year I intended to continue taking record shots alongside my own photography so that I could carry on providing data for the site's records. I had no idea at this point, the rabbit hole that I would find myself going down.

A combination of curiosity and a rainy weekend lead me to look a little deeper into my photographic records. It occurred to me that although last year I had started to make a log of the individuals I had seen, there was a whole archive of potentially useful images at my disposal, to catalogue adders from even further back. My inability to delete photos and to fill up hard drive after hard drive with images (that I will never use but cannot bring myself to get rid of) really came into its own for this. Slowly but surely I worked my way through my images and began to identify them.

The head pattern of an adder is widely used to identify individuals as it’s as unique to them as a fingerprint is to us. This is probably more relevant to the kind of surveys where the adder is caught, put in a tube and then uniform close-up photos can be easily taken. When you’re taking record shots only and want to cause no disturbance to the snake at all, head pattern isn’t my preferred ID method. You very rarely get an opportunity to take a clear, straight on, close-up shot of the head. You normally end up taking a photo slightly off to one side, dictated by the positioning of the snake and/or its surroundings. So the head and zig zag markings below it are often distorted in photos, meaning they are less useful. The differences in head patterns are often subtle and there isn’t enough variation between them in general, to be able to quickly separate individuals, even if you have good quality photos. There are other more obvious features to look for which speeds up this process.

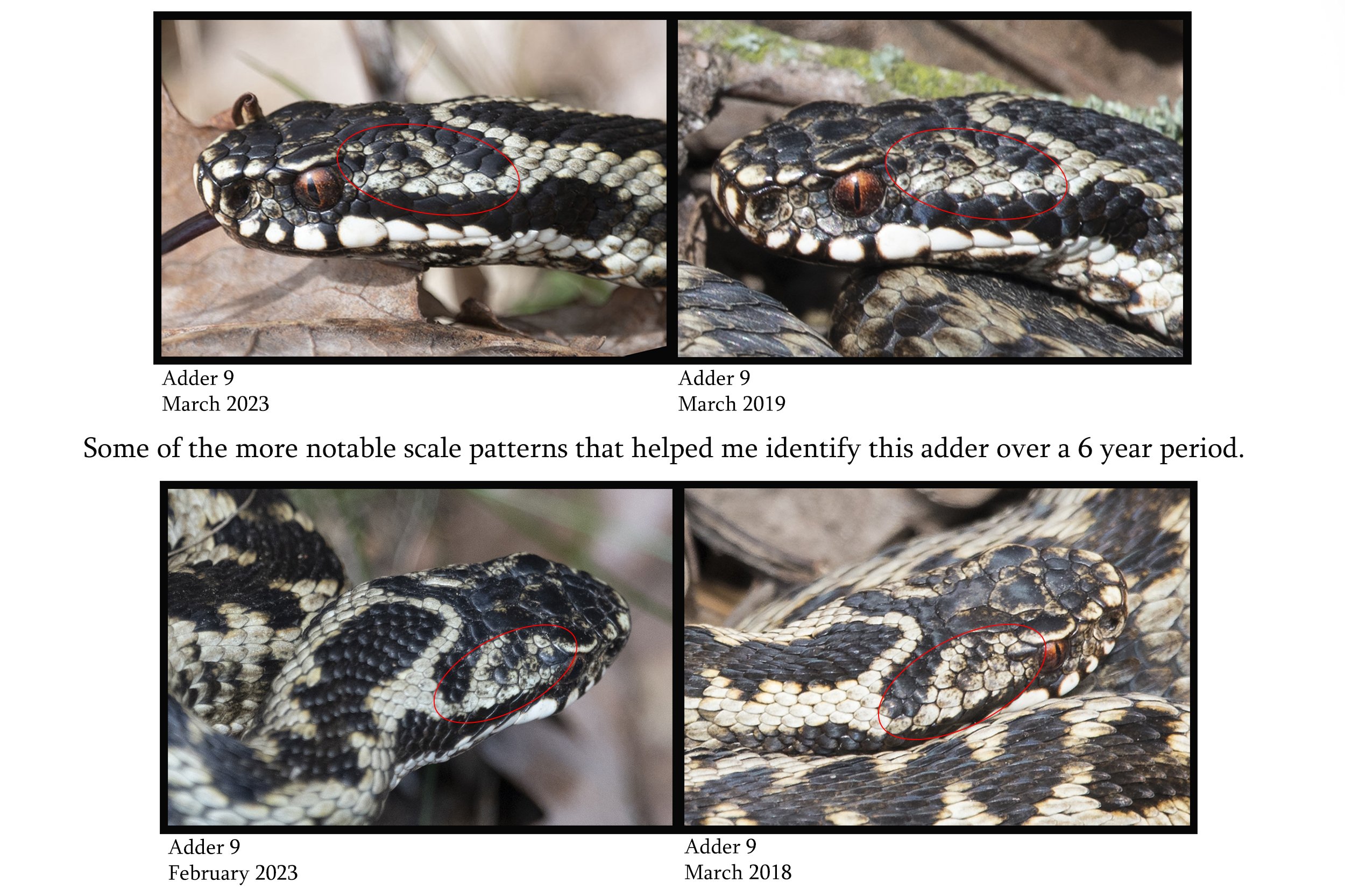

The head pattern may be unique to each individual but so is their entire scale arrangement. This is most obvious when viewing the snakes head side-on. The features that helped me distinguish between individuals are best illustrated with photo comparisons.

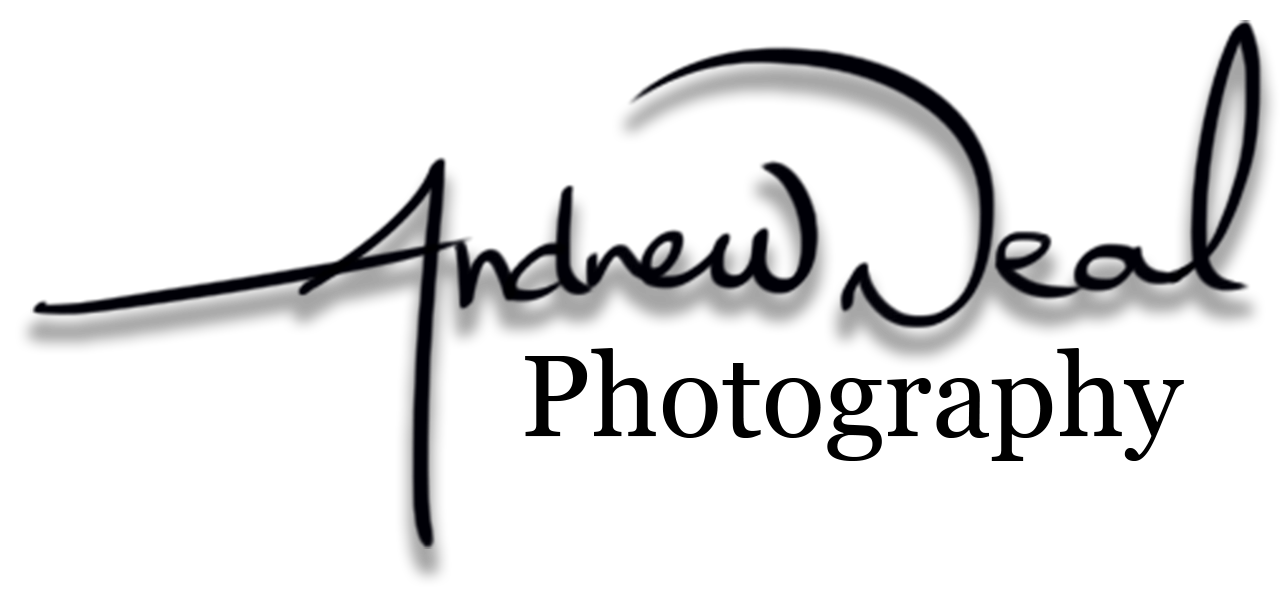

The scales along the upper lip (supralabials or upper labials) are probably the easiest way to quickly distinguish between males, often without the need to use any other features. The shapes that are created by the black lines and patterns on the white labial scales are very rarely similar enough to cause confusion between two individuals. The dark lateral marking that runs from the eye, above the labial scales, can also bring out some distinctive patterns where the black and white intersect one another.

The labial scales are still useful for distinguishing between females but they are not as obvious. Rather than the strong black and white of the males, the females markings are a much more subtle gingery orange colour. This tends to be the same for the various scales around the snout where the females will have little to no markings compared to the more defined patterns found on the males.

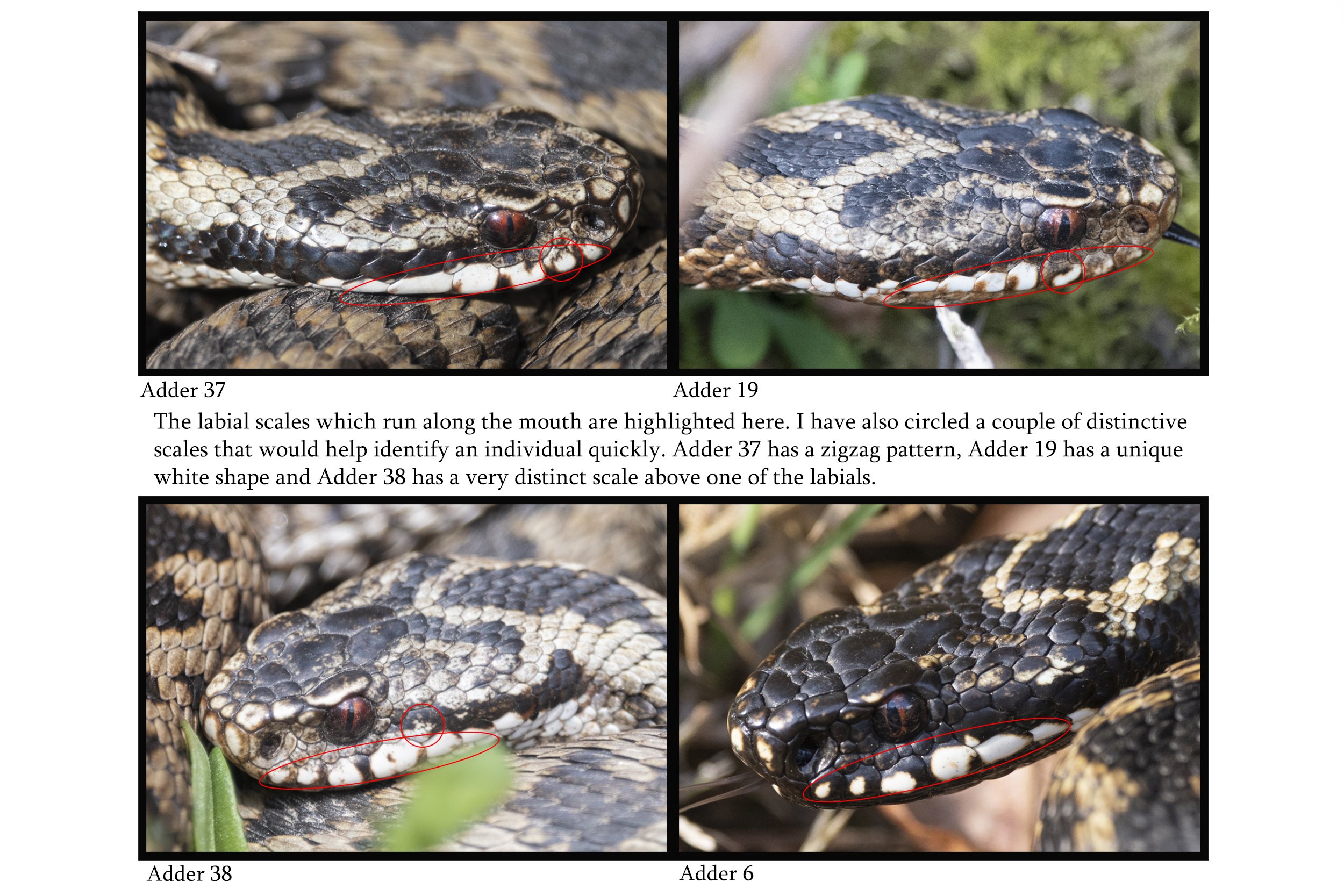

I’ve read that some people use the rostral scale as a way of distinguishing male and female adders, with the edges having a more defined patterned border in the males. There are always exceptions to the rules, however and the general consensus is that this should be treated as more of a guide, alongside more full proof sexing methods, than a deciding factor on its own.

The nasal scale, where the nostril is located, and its surrounding scales are useful to look at. These and the ocular scales, around the eye, vary in shape and quantity.

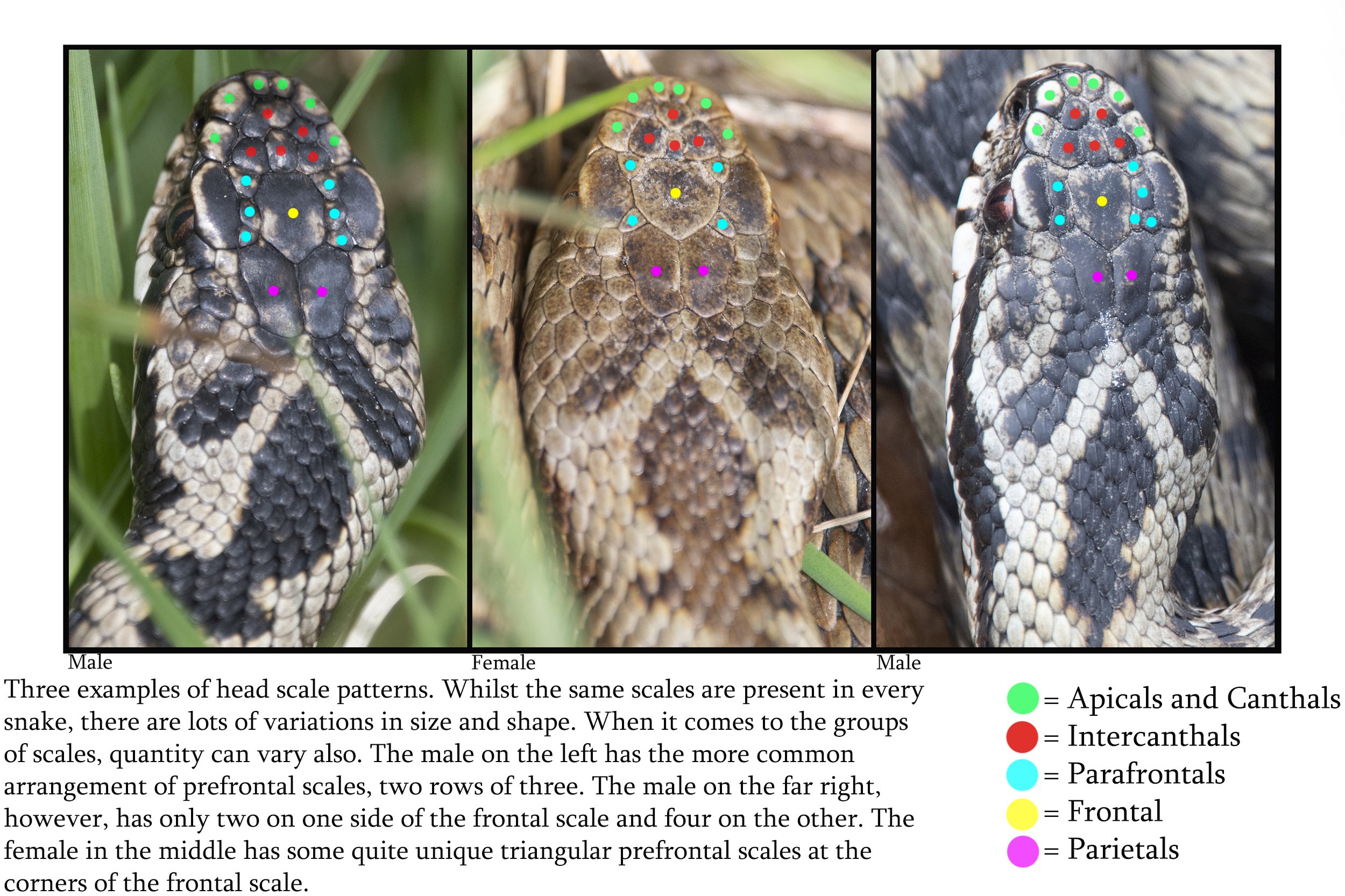

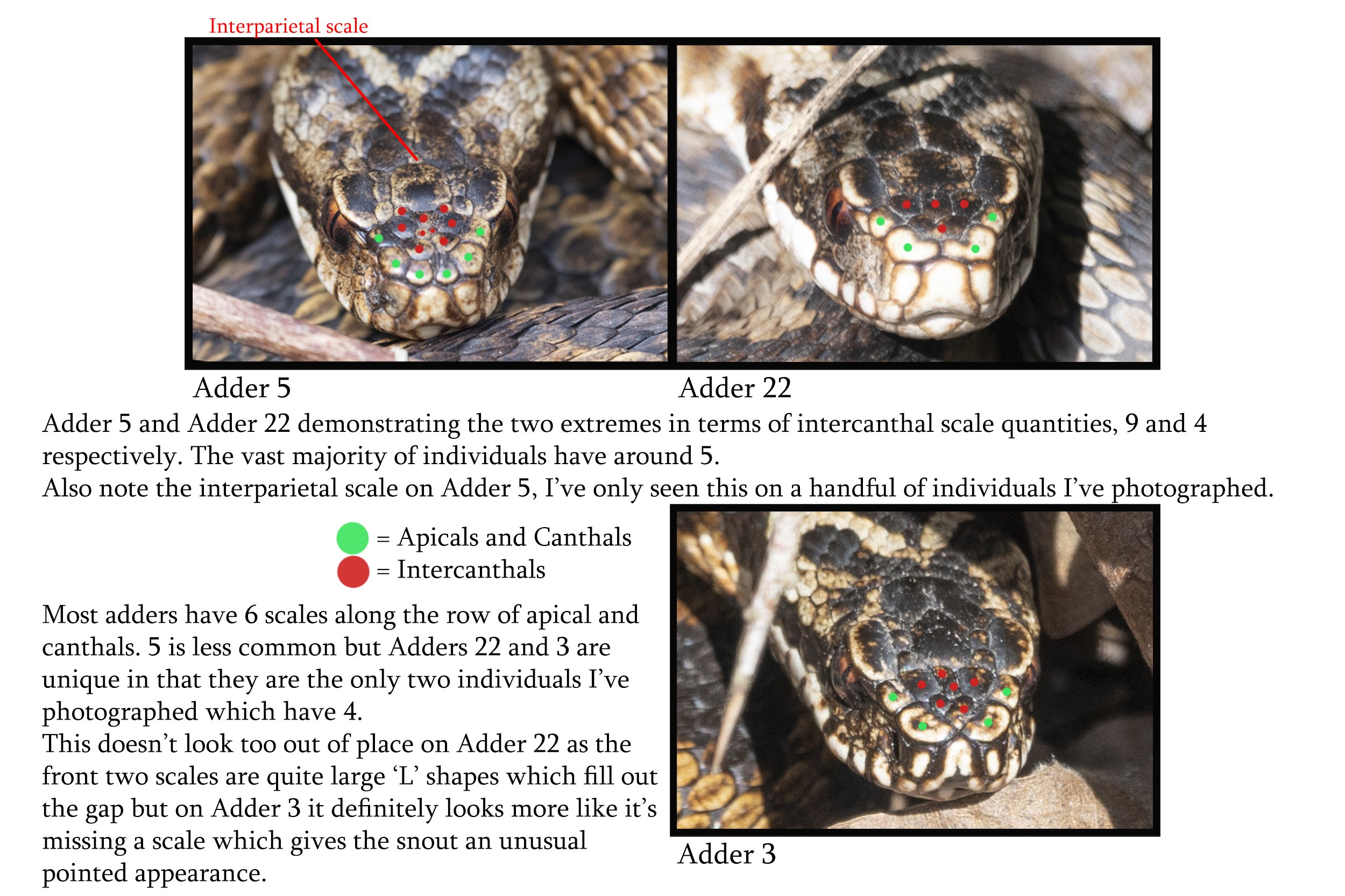

I mentioned earlier about the head pattern not being the first thing I look at when distinguishing between individuals but it is still important. The actual scale arrangements on the top of the head, in particular, are very useful. Although there are specific scales found on all adders, there is an enormous amount of variation in some of these scale arrangements and again, no two are the same.

The scale pattern on the head helps to connect photos taken of either side of the adder's head. You are normally shooting from slightly above even when capturing one side of the head, so the scales on top are also visible to an extent. This helps you match one side to a photo looking at the top of the head which in turn helps match that to the other side. Those are the three angles I try to capture, if possible and a snout on view can also be useful as an additional aid.

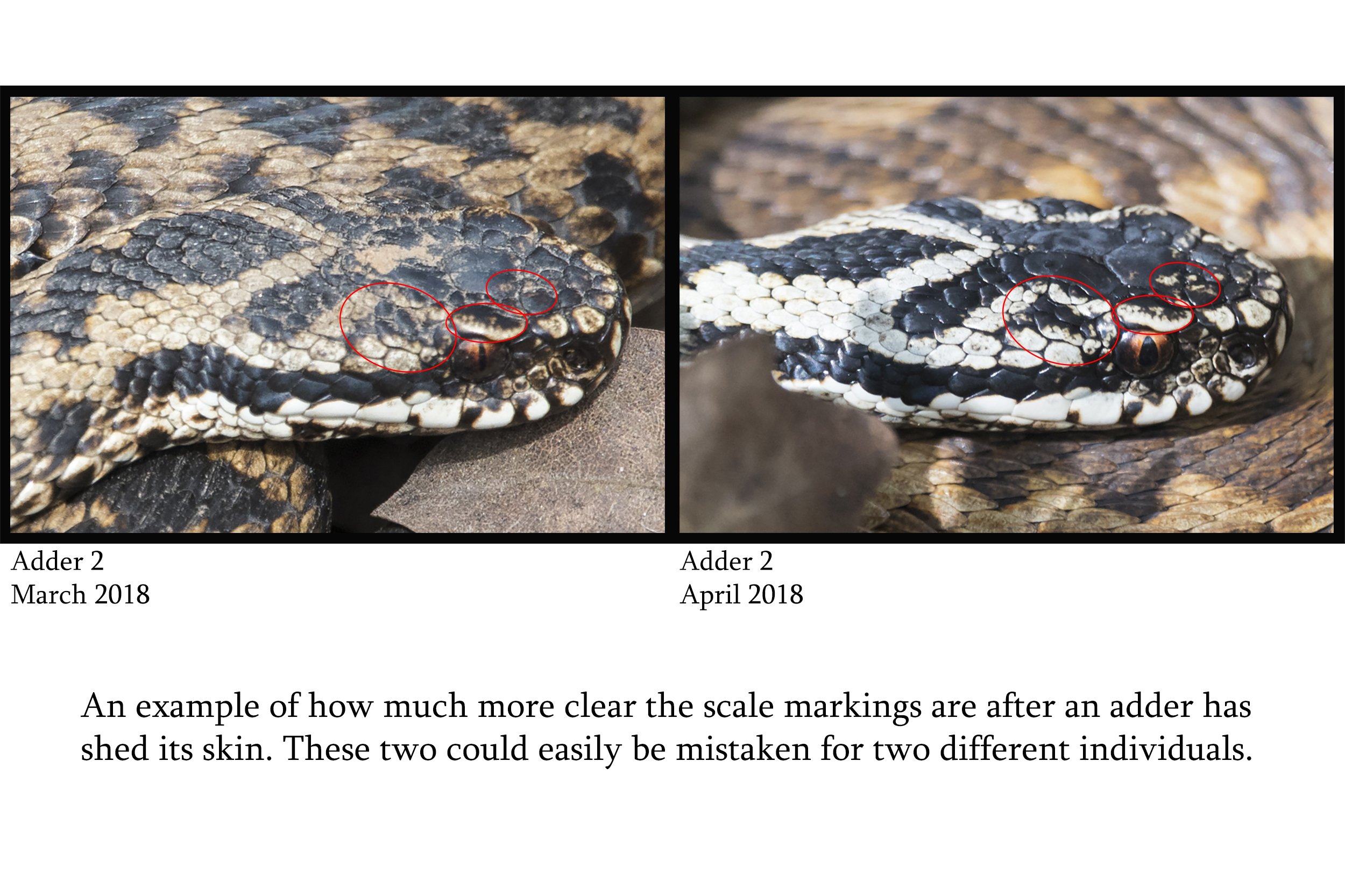

It’s worth mentioning that scale patterns and markings will fade or become less obvious over time. They are at their most vivid after the snake has shed its skin. This can cause a little confusion if you find the same individual at different points in a year or over a number of years.

Using these features to identify individuals, I was able to catalogue all the adders I’ve photographed from 2016 to 2023. I gave each of them a number and as of the time of writing I am up to 50 different individuals spanning across the 8 years (although 2020 and 2021 are very limited due to the covid restrictions)

As well as providing useful data for the site, cataloguing individuals has helped shed a bit more light on the adders behaviour. I have spent a lot more time watching the adders this spring, partly due to the added intrigue created by my extra research and partly because my two regularly used lenses were both away having some work done on them. So with the emphasis being more on observing and only being able to capture record shots, the adders have been the ideal subject to spend even more time with than normal.

Adder 9 was the first individual to emerge from hibernation this year, on the 19th of February, the first time I had seen it since 2019.

With spending extra time observing the adders this year I was hoping I would witness the adder ‘dance’ again, where two males battle over a female. I have only seen this once, last year, and it was a real spectacle. The larger male was victorious in the scuffle and chased off the smaller male before returning to the female. The following day I found the female in the same spot coiled up with what I assumed was the same male. With the help of my record shot cataloguing, I discovered that the male who actually ended up with the female was the one that lost the battle the previous day and was chased off. In this instance what the adder lacked in size and strength, it made up for with persistence.

Unfortunately I didn’t get to witness a battle this year. The closest I got was when a new male to the area chased off two of the regular males that were out basking. This new male had recently shed its skin, unlike the other two males it chased off. So their priority at this stage was to bask in preparation for when they shed their skin. Very different to the priorities of this other male, who had found two females nearby and only saw these males as competition. There was no need or benefit, at this point, for the other males to stand their ground.

I’d only found one shed skin in the past 8 years of observing the adders but this year I found four. One of which I must have only missed being shed by a matter of minutes as the skin was still almost rubbery to the touch and hadn’t fully dried to the crisp texture you normally see them in. Something I did find out this Spring was just how quickly the male adders go off in search of a female after shedding. It’s almost like an internal switch goes off. After weeks of basking in the same spot all day, once they shed their skin, they would only be there for a maximum of one extra day before going off to search for a female. I would only see them again if it was with a female and if she wasn’t receptive to his courtship attempts, he would move on in search of another.

It’s no mystery that adders don’t venture far from their hibernaculum during the first few weeks of emerging. One area in particular was once a regular spot for a handful of adders to bask and it would be pretty common to see four males out, soaking up the sun at the same time. Adder 1, for example, I photographed at the same spot in 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020. There were other individuals that I recorded there a similar amount of times over multiple years.

What was a surprise to me when matching up the record shots was just how far the males will travel to find a female. In April 2018 I found Adder 2 mating with a female, 128 metres away from its hibernaculum. Also in May of that same year I found Adder 1 mating with a female whilst Adder 6 basked nearby, on a different part of the site, 305 metres from their hibernaculum. They had obviously both followed the scent of the same female to end up in the same spot. All of these male adders were found back at their hibernaculum the following Spring so these trips out to find a mate are all return journeys.

The longest distance I have recorded a male adder travelling was this year. In April I found a new individual, Adder 45, basking with two other males which I had been watching regularly at a new area of the site. A week later, at a different area of the site, I saw a male engaging in courtship behaviour with a female. When I checked the photos back on the computer, I couldn’t believe that it was the same male I had seen a week ago as this pair were 677 metres away from where I had seen it. This helped put to bed concerns I had previously about the individual populations of adders on site becoming isolated. This distance of nearly half a mile covered virtually the entire length of the site, from one corner to another. With there being considerably less females present, it’s reassuring to know that the males do find them, however far away they are.

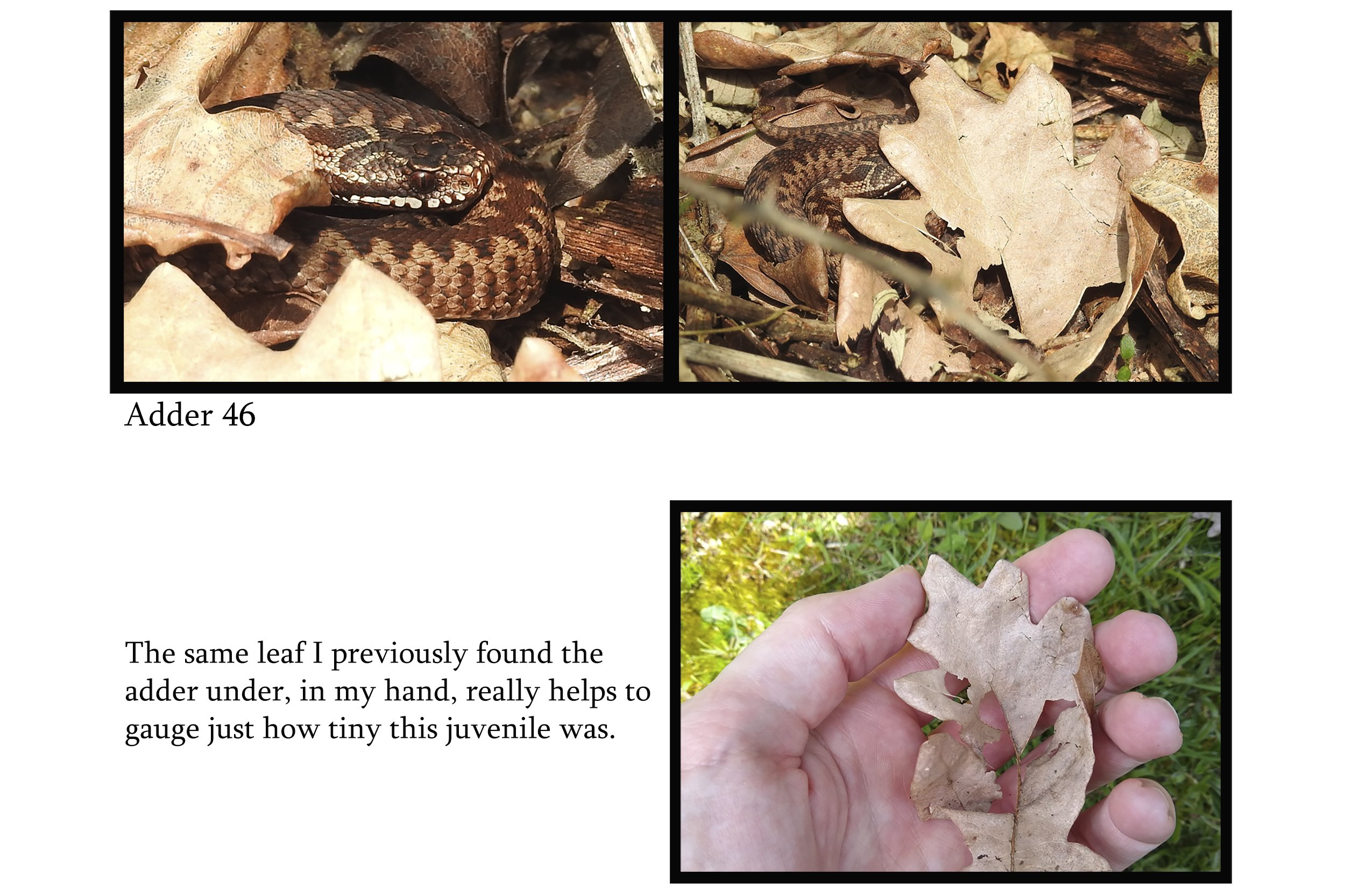

It was also reassuring that the very last individual I saw basking, after all the others had moved off to find a mate, was a juvenile.

Judging by its size, it was probably born at the end of the previous Summer. Hopefully this was one of many and that the population which has noticeably dwindled over the years, can pick back up over time. Perhaps I’ll be able to use the photos I took of this baby adder in the future and identify it again as an adult.